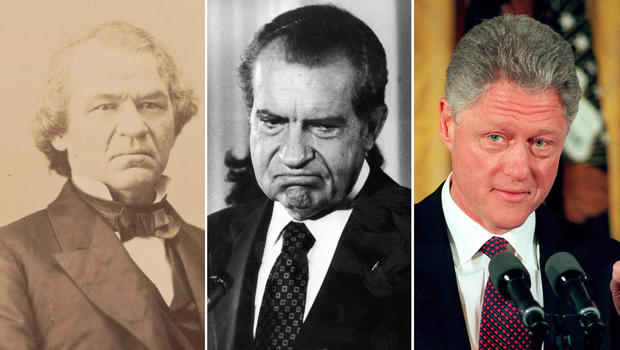

What have presidents been impeached for? The articles of impeachment for Andrew Johnson, Richard Nixon, Bill Clinton and Donald Trump

There have been only four presidential impeachments in U.S. history. In the past year, Americans have lived through half of them.

The second impeachment trial of former President Donald Trump finished on February 13 — just one year and eight days after his first trial ended. Mr. Trump was acquitted again, but he also pushed the boundaries for the nation's slim history of presidential punishments. Mr. Trump is the first federal official to be impeached twice and the first president to face a trial after leaving office, and his impeachments broke two records for senators voting against the president of their own party.

Before Mr. Trump, only two presidents had been impeached — Andrew Johnson in 1868, and Bill Clinton in 1998. Neither was convicted. Richard Nixon resigned in 1974 after articles of impeachment were drafted, but before the House could vote on them.

The Constitution says presidents and other federal officials can be impeached for "Treason, Bribery and other High Crimes and Misdemeanors." No president has faced impeachment articles for treason or bribery; all impeachment cases so far came down to what Congress considered to be "High Crimes and Misdemeanors."

The phrase "High Crimes and Misdemeanors" is not defined in the Constitution, leaving it up to Congress to decide what qualifies in any particular case. Historians and legal scholars say it's generally understood to mean a serious abuse of the public trust.

Here's a look at what led to past presidents facing impeachment.

How impeachment works

The House has the power to impeach the president, and the Senate, in a subsequent process, then decides whether to remove an impeached president from office. The Senate can also hold a separate vote on whether to ban the president from holding office again.

The House drafts articles of impeachment outlining the president's alleged offenses, and can vote to impeach him with a simple majority vote on any of the articles. However, impeachment in the House is not enough to remove or disqualify a president from office.

The Senate then holds an impeachment trial, and ultimately votes on whether to convict or acquit the president on the articles approved by the House. A two-thirds majority of senators (at least 67) would need to vote for convicting the president, leading to his removal and potential ban from public office.

Andrew Johnson

What happened?

The 17th president was the first to be impeached.

Johnson, a Democrat from Tennessee, was President Abraham Lincoln's running mate for Lincoln's second term. Just 42 days after becoming vice president, Johnson ascended to the presidency following Lincoln's assassination in April 1865. This put him in charge of a country still reeling from the Civil War, and he was soon clashing with Congress over how to handle Reconstruction.

Johnson favored a lenient approach to the former Confederate states and shocked lawmakers with some of his vetoes, including his veto of a bill that would have provided food, shelter and aid to newly freed African Americans and Southern refugees.

The final straw came in 1868, when Johnson fired Secretary of War Edwin Stanton, a Lincoln appointee who opposed Johnson's approach to Reconstruction. House Republicans said this violated the Tenure of Office Act, a law passed one year earlier that said the Senate must approve the president's dismissal of a Cabinet member he appointed. (Johnson vetoed that bill, but Congress overrode him. The Supreme Court ruled in 1926 that the Tenure of Office Act was invalid, and it is no longer enforced.)

What did the impeachment articles say?

In February 1868, the House voted in favor of an impeachment resolution against Johnson. A week later, the House adopted 11 articles of impeachment.

Most of the articles centered on Johnson's dismissal of Stanton, alleging that the move defied the Senate and violated the Constitution. One article accused Johnson of unlawfully ordering that all military orders had to come from the General of the Army.

Another article said Johnson gave speeches that attempted "to bring into disgrace, ridicule, hatred, contempt and reproach, the Congress of the United States." That article said Johnson had declared "with a loud voice, certain intemperate, inflammatory and scandalous harangues," and that he had uttered "loud threats and bitter menace" toward Congress.

The text of the impeachment articles repeatedly said that Johnson was "unmindful of the high duties of his oath of office."

What was the outcome?

Only three of the impeachment articles were voted on by the Senate — two about the appointment of Stanton's replacement, and one about insulting and disrupting Congress.

On each of these three articles, the Senate acquitted Johnson by a single vote. He remained in office until 1869, leaving after one term when he failed to win his own party's nomination.

Richard Nixon

What happened?

Nixon, a Republican, resigned before facing a formal impeachment vote. But he was the first president since Johnson to have impeachment articles drafted against him.

The impeachment process for Nixon started in October 1973, after the Watergate scandal had dragged on for more than a year.

Nixon resisted House subpoenas as the Watergate investigation intensified. The impeachment process began just days after the "Saturday Night Massacre," when Nixon fired the special prosecutor investigating Watergate, Archibald Cox, and accepted the resignations of Attorney General Elliot Richardson and Deputy Attorney General William Ruckelshaus.

In the impeachment proceedings, Nixon was not directly implicated in the break-in of the Democratic National Committee headquarters in Washington. Rather, the focus was on his efforts to obstruct the Watergate investigation.

What did the impeachment articles say?

The House Judiciary Committee approved three articles of impeachment against Nixon in July 1974.

The first said Nixon had worked with subordinates to "delay, impede, and obstruct the investigation" into the Watergate break-in to "cover up, conceal and protect those responsible; and to conceal the existence and scope of other unlawful covert activities."

The second article said the president had "repeatedly engaged in conduct violating the constitutional rights of citizens" by "impairing the due and proper administration of justice and the conduct of lawful inquiries."

The third article focused on Nixon's resistance of subpoenas from the House committee. It said the president had "interposed the powers of the Presidency against the lawful subpoenas of the House of Representatives, thereby assuming to himself functions and judgments necessary to the exercise of the sole power of impeachment vested by the Constitution in the House of Representatives."

What was the outcome?

The House Judiciary Committee approved all three articles, but the articles never reached a full House vote. An impeachment seemed inevitable after the U.S. Supreme Court ordered the White House to release the tape of a phone call that showed Nixon had ordered a cover-up of Watergate. Even the Republican House leader said he would vote to impeach Nixon.

Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974. He became the first, and so far only, U.S. president to resign. And even though he was not technically impeached, he was also the first and only president to leave office due to an impeachment process.

One month later, Nixon's successor, President Gerald Ford, granted Nixon a full pardon for any crimes he may have committed as president, ensuring that he wouldn't face punishment out of office. Ford argued that an end to the Watergate saga was in the country's best interest.

Bill Clinton

What happened?

More than 130 years after Johnson's impeachment, Clinton, a Democrat, became the second president to be impeached.

Clinton's impeachment process sprouted from the Starr Report — the result of a four-year independent counsel investigation into his administration — and from a lawsuit filed by Paula Jones, a woman accusing Clinton of sexual misconduct.

In a deposition for the Jones lawsuit, Clinton falsely claimed that he did not have a sexual relationship with White House intern Monica Lewinsky. The Starr Report said Clinton tried to cover up his affair with Lewinsky, and had pressured his secretary Betty Currie to repeat his denials.

What did the impeachment articles say?

The Republican-held House drafted four articles of impeachment against Clinton, but only two were approved.

The first article that passed said Clinton had provided "perjurious, false and misleading testimony" to a grand jury in the Jones case. It was approved in a 228–206 vote.

The second approved article, which passed with a 221–212 vote, said Clinton had "obstructed justice in an effort to delay, impede, cover up and conceal the existence of evidence related to the Jones case."

An article for a second perjury count, and another article accusing Clinton of abuse of power, failed to get a majority vote.

Clinton was impeached in December 1998. At least one Democrat voted for each of the four impeachment articles, and five Democrats voted for the two that were ultimately passed.

What was the outcome?

A Republican-controlled Senate acquitted Clinton on both charges in February 1999. The Senate trial resulted in 45 "guilty" votes for perjury and 50 "guilty" votes on obstruction — both short of the two-thirds vote needed to convict and remove the president.

All 45 Democrats in the Senate voted "not guilty" on both charges, and several Republicans joined them, with some arguing that Clinton did not deserve to be removed from the White House for these offenses.

Clinton remained in office and completed his second term.

Donald Trump — First impeachment

What happened?

Some congressional Democrats, as well as protesters nationwide, began calling for President Trump's impeachment right after he took office. But it took an anonymous whistleblower complaint, in the third year of his presidency, to eventually make it happen.

The complaint filed in August 2019 sounded the alarm about a phone call Mr. Trump had with another world leader. A month before, Mr. Trump had asked the new Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky in a phone call to "do us a favor" and pursue politically-loaded investigations, while withholding U.S. military assistance that had been approved by Congress.

One issue the president raised involved a disproven conspiracy theory that Ukraine somehow interfered in the 2016 election. He also pressed for an investigation into former Vice President Joe Biden — then a frontrunner in the Democratic presidential primary — and his son, Hunter, who held a paid position on the board of Ukrainian gas company Burisma while his father was vice president.

Earlier in July, Mr. Trump had ordered a freeze on $391 million in security aid to Ukraine that Congress had approved. The U.S. ultimately released the aid in September, after the whistleblower complaint, and Ukraine never launched either investigation.

Days after news of the whistleblower complaint emerged, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi launched a formal impeachment inquiry in the Democrat-controlled House. During the hearings that followed, former and current Trump administration officials testified about an irregular diplomatic channel in Ukraine involving the president's personal attorney, Rudy Giuliani, and stressed that the freeze on aid undermined American and Ukrainian national security.

Gordon Sondland, the U.S. ambassador to the European Union, testified that there was a "quid pro quo" conditioning the security aid and a White House meeting on Mr. Trump's requests to Zelensky.

During the inquiry, the White House refused to comply with House subpoenas for documents and witness testimonies. The president insisted that his call with Ukraine's president was "perfect."

What did the impeachment articles say?

House Democrats settled on personal attorney: Abuse of power and obstruction of Congress.

The abuse of power article said Mr. Trump had "openly and corruptly" solicited political investigations from Ukraine and conditioned official acts on his requests. "President Trump engaged in this scheme or course of conduct for corrupt purposes in pursuit of personal political benefit," it said.

The obstruction of Congress article cited Mr. Trump for withholding documents and ordering officials to not testify. "In violation of his constitutional duty to take care that the laws be faithfully executed — Donald J. Trump has directed the unprecedented, categorical, and indiscriminate defiance of subpoenas issued by the House of Representatives pursuant to its 'sole Power of Impeachment," it said.

Mr. Trump's Republican defenders criticized the articles as partisan and political, noting that abuse of power and obstruction of Congress are not criminal offenses. They also criticized House Democrats for rushing the process instead of waiting for courts to rule on the subpoenas.

What was the outcome?

On December 18, 2019, the House impeached Mr. Trump on both articles. The votes were 230-197 for abuse of power, and 229-198 for obstruction of Congress. At the time, those were the two highest vote tallies ever in support of impeachment articles.

No Republicans voted in favor of either article. Two Democrats voted against the abuse of power article, three voted against the obstruction article, and one (Tusli Gabbard, who was also running for president) simply voted "present" for both.

The Senate trial's opening arguments began January 22, and the trial concluded just two weeks later. Republicans controlled the Senate with 53 votes, and used that power to keep the trial as short as possible.

A majority of 51 Republicans voted against allowing subpoenas for additional documents or calling witnesses, one of whom would have been John Bolton, Mr. Trump's former national security advisor. Bolton published a memoir later in 2020, in which he confirmed the accusation that Mr. Trump withheld Ukraine's military aid to pressure the government into investigating the Bidens.

On February 5, the Senate acquitted Mr. Trump on both charges. The votes were 52-48 on abuse of power, and 53-47 on obstruction of Congress. Republican Senator Mitt Romney of Utah voted to convict Mr. Trump on the abuse of power charge — becoming the first senator to ever vote against a president of his own party in an impeachment trial.

Mr. Trump held a ceremony at the White House the next day celebrating his acquittal in a profanity-laced speech.

Donald Trump — Second impeachment

What happened?

Nine months after his acquittal, Mr. Trump lost the 2020 presidential election to Joe Biden. But the president refused to concede.

In the two months after the election, Mr. Trump insisted he won the race and spread false conspiracy theories about election fraud. His legal team filed dozens of challenges to the election results, all of which were shot down in court. His falsehoods set off a "Stop The Steal" movement of supporters who wrongly insisted the election was rigged and sought to overturn the results.

Mr. Trump held a "Save America" rally on the National Mall on January 6, 2021, the day Congress met for its ceremonial counting of Electoral College votes confirming Mr. Biden's victory. The president told his supporters about 20 times to "fight" the election results, and said they should "demand that Congress do the right thing and only count the electors who have been lawfully slated." He urged supporters to walk down to the U.S. Capitol and said he would go with them, but he didn't go.

Thousands of supporters from the rally then marched to the U.S. Capitol, and hundreds broke through police lines and stormed the building to disrupt the vote count. Capitol Police evacuated Congress members as the rioters assaulted officers, ransacked offices and chanted for the deaths of lawmakers, including Vice President Mike Pence, whom Mr. Trump falsely claimed could overturn the election results.

The insurrection led to five deaths, including a Capitol police officer, Brian Sicknick, who died from injuries sustained in the attack.

During the Capitol assault, Mr. Trump posted a video on Twitter telling supporters, "We have to have peace. So go home. We love you. You're very special." He still claimed the election was "fraudulent" and did not explicitly denounce any of the violence.

After several hours, the rioters were cleared from the Capitol, and Congress reconvened to the complete the vote count — the final step in confirming Mr. Trump's defeat.

What did the impeachment articles say?

Lawmakers in both parties blamed Mr. Trump for fueling the violence. Just five days after the attack, the Democrat-controlled House introduced an article of impeachment for incitement of insurrection.

The article condemned Mr. Trump for his remarks before the riot as well as his earlier efforts to subvert his election loss, including a call to Georgia's secretary of state asking him to "find" votes to flip the state for Mr. Trump.

"In all this, President Trump gravely endangered the security of the United States and its institutions of government," the article states. "He threatened the integrity of the democratic system, interfered with the peaceful transition of power, and imperiled a coequal branch of Government." It said Mr. Trump would be "a threat to national security, democracy, and the Constitution if allowed to remain in office," even though he only had a few days left.

The House voted 232-197 to approve the article on January 13, one week before the end of Mr. Trump's term. Ten Republicans joined all Democrats in the vote, making it the most bipartisan impeachment vote in U.S. history. It was also the highest vote tally ever in support of an impeachment article — breaking the previous record from Mr. Trump's first impeachment.

This second impeachment raised the unprecedented questions of whether a former president could even face a Senate trial, and what kind of punishment he would get if convicted. The Constitution does not directly address these issues, but most constitutional scholars agreed that officials can face impeachment trials even after they have left office.

The primary historical example is William Belknap, the secretary of war under President Ulysses S. Grant, who in 1876 handed in his resignation and burst into tears just minutes before the House was set to vote on impeaching him for a kickbacks scandal. The House still unanimously approved five impeachment articles, and the Senate held a trial, where Belknap was ultimately acquitted on all charges.

With Mr. Trump already removed from office through an election, Democrats said they could ban him from running for office again, which would have required a separate vote after his conviction.

What was the outcome?

The Senate trial began February 9, and wrapped after just five days — a swift end for the fastest impeachment process on record. On the trial's first day, the Senate decided in a 56-44 bipartisan vote that the trial was indeed constitutional.

Democratic impeachment managers relied heavily on video evidence for their arguments. They played never-before-seen footage from the Capitol attack, showing how close lawmakers had come to facing a violent mob, along with videos of Mr. Trump encouraging violence during his presidency and campaign rallies. Mr. Trump's defense focused largely on challenging the process of trying a former president, and argued against directly connecting him to the Capitol violence.

On the trial's final day, the Senate voted to allow witnesses and more evidence — a move that could have prolonged the trial for weeks or months. But just two hours later, impeachment managers and Mr. Trump's lawyers reached an agreement to proceed to the trial's conclusion. One impeachment manager, Representative Joe Neguse of Colorado, later told CBS News' "Face The Nation" that he believed more witnesses "would not have made a difference" for most Republican senators.

In the end, the Senate acquitted Mr. Trump with a vote of 57 "Guilty" to 43 "Not Guilty" — 10 votes short of the two-thirds majority needed for conviction. Seven Republicans voted against Mr. Trump — Richard Burr of North Carolina, Bill Cassidy of Louisiana, Susan Collins of Maine, Lisa Murkowski of Alaska, Mitt Romney of Utah, Ben Sasse of Nebraska and Pat Toomey of Pennsylvania. It is the highest number of senators to vote for convicting their own party's president, breaking another record from Mr. Trump's first impeachment.

Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell voted to acquit Mr. Trump but still blamed him for the Capitol riot in a scathing speech immediately afterwards, saying there was "no question" the former president is "practically and morally responsible" for the riot. The Kentucky Republican said his acquittal vote came from his decision that the Senate did not have constitutional grounds to convict an ex-president.

McConnell, however, said Mr. Trump was not immune from being punished by the country's criminal and civil laws.

"He didn't get away with anything yet," he said. "Yet."

for more features.